Divergent and Convergent Thinking

There are two distinct thinking modes—divergent and convergent—that help us to problem solve successfully and creatively. We can use them in classrooms every day, but we often don’t! These two thinking modes are a dynamic duo - we need them both, and they each have their own time to shine.

What does it take to be a creative problem solver? We all know that there are some enormously complex problems in the world that we must address. Will today’s students be prepared to tackle the big problems of the future with the creative solutions we’ll need? Can we help them to become creative thinkers? We certainly think so!

There are two distinct thinking modes that help us to problem solve successfully and creatively. We can use them in classrooms every day, but we often don’t! These two thinking modes are a dynamic duo - we need them both, and they each have their own time to shine. They go like this:

Divergent thinking comes first. This is when you open up possibilities. You come up with as many ideas as you can, you spitball, you throw out wild options! Diverging is open, free, explorative.

Then comes convergent thinking. This is when you evaluate your options, strengthen ideas, and narrow down to the best solution. Converging is careful, discerning, and selective.

To use this dynamic duo of thinking in the classroom, we need to give students the opportunity to address open-ended challenges, not just questions that have one right answer. Furthermore, we need to show them how to use divergent and convergent thinking to get creative!

“The important thing to remember is that divergent and convergent thinking have to be separate.”

The important thing to remember is that divergent and convergent thinking have to be separate. You can’t judge your ideas before you let yourself freely explore as many ideas as you can, because creative ideas often seem unusual at first and might get dismissed. When diverging, there’s no such thing as a bad idea.

Here are the rules for divergent thinking:

Wait to judge ideas.

Aim for lots of ideas.

Go for wild ideas.

Build on other ideas.

Once you have an abundance of ideas to work with, then you can start to think about which might be workable solutions.

Here are the rules for converging:

Come at ideas positively.

Take time to consider.

Remember your original purpose.

Improve ideas.

Keep unique options alive.

In classrooms, we’re often not accustomed to allocating time for divergent thinking, but if we encourage it, and combine it with convergent thinking, the result can be amazing, creative work. What’s more, students can start to realize their power in solving problems with creativity.

Can you think of a way to utilize divergent and convergent thinking in your classroom? How about thinking of a lot of ways, and then narrowing it down? We’d love to hear your ideas!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sara Smith is an educator, learner, and creativity consultant for FableVision Learning. She holds a Master of Science in creativity from the International Center for Studies in Creativity at SUNY College at Buffalo. Sara is compelled by learning and its intersection with creativity, and her vision is to develop and support creative communities that help people to grow and to nurture their passions and strengths.

References:

Rules for divergent and convergent thinking are adapted from Miller, B., Vehar, J. R., Firestien, R. L., Thurber, S., & Nielsen, D. (2011). Creativity Unbound: An Introduction to Creative Process. (5th ed.). Williamsville, NY: Innovation Resources.

Beghetto’s "Beautiful Risks": A Review

What risks have you taken lately in your classroom? Are you more likely to see risks as reckless or worthwhile?

In Beautiful Risks: Having the Courage to Teach and Learn Creatively, Dr. Ron Beghetto describes how we can look at, and think about, risk-taking in our classrooms so as to minimize the hazards and optimize the benefits.

What risks have you taken lately in your classroom? Are you more likely to see risks as reckless or worthwhile?

In Beautiful Risks: Having the Courage to Teach and Learn Creatively, Dr. Ron Beghetto describes how we can look at and think about risk-taking in our classrooms so as to minimize the hazards and optimize the benefits. Good risks are ones in which the personal benefits outweigh the negatives, bad risks are just the opposite, but it’s the beautiful risks that are the focus of this book. These are risks that have the potential to lead to creative contributions that benefit the whole classroom community.

Establishing and maintaining a creative classroom is a beautiful risk. There is no exact step-by-step process for it, and creativity inherently involves uncertainty and ambiguity. But there are substantial benefits to having a classroom in which students generate and share new thinking, and have the confidence to create. It is worth learning when and how to take the beautiful risks necessary (and when not to!).

With a firm grasp on the balance teachers must walk between pedagogical experimentation and their content standards obligations, Beghetto provides a measured approach and a gentle nudge to open up classrooms and curricula for creativity. Each chapter addresses the potential costs and benefits to the beautiful risk described in addition to providing examples to take ideas from theoretical to practical.

Prepare to embrace uncertainty, get brave enough to “go off script,” and learn to plan creative openings in your daily lessons. This book is perfect for the careful educator who wants to incorporate more creativity into his or her classroom, but is concerned about doing so responsibly. Here we share our favorite three takeaways:

We can take beautiful risks in the way we respond to students’ unusual ideas and answers in the classroom, which Beghetto calls “curricular ruptures.” Instead of just saying “No” to an incorrect answer and moving to the next student, we can take a moment to explore the student’s thinking. When we let ourselves “go off script,” we give room for students to share their creative thoughts, which increases creative confidence and potentially enriches the learning of all the students. At the same time, the author models weighing the costs and benefits so that we can learn to recognize when to take the risk and when we might not want to.

Many of us overplan in the attempt to ensure we are prepared with an appropriate lesson. The problem with overplanned lessons is that they often have the task, the process, and the outcome clearly defined, leaving little to no room for creative input from the students. Beghetto encourages taking an overplanned lesson and leaving out one or more aspects of the required components (the task, the process, or the outcome) in order to open up the lesson for creativity. Instead of trying to come up with a whole new curriculum, this is a simple way to start incorporating creativity into your teaching.

Our intentions in the decisions we make in the classroom are not always how they are perceived by our students. Within the beautiful risk of establishing a creative environment, we must be careful to address the potential hazard of our students interpreting our actions in ways that stifle their creativity. This may include our classroom management system or the way that we track students’ goals and progress. Beghetto provides the example of a data board that tracks student progress in a fun, seemingly engaging way, but because it rewards quick progress and correct answers, it actually discourages students from taking their time and coming up with novel, challenging ideas. We must check in with students and work to ensure their experience reflects the value we want to place on creative expression.

After reading this book, perhaps you’ll feel empowered to bring even more creativity into your teaching. Let us know what beautiful risks you take!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sara Smith is an educator, learner, and creativity professional. She holds a Master of Science in creativity from the International Center for Studies in Creativity at SUNY College at Buffalo. Sara is compelled by learning and its intersection with creativity, and her vision is to create and support creative communities that help people to grow and to nurture their passions and strengths.

CITATIONS:

Beautiful Risks: Having the Courage to Teach and Learn Creatively,

Using Mood Structures to Support Student Writers

A post by Trevor Bryan

When it comes to discussing stories, Mood is by far my favorite word. Why? Because almost all stories, fictional or not, are built around moods.

Whether you are watching a play, an animated movie, or reading a story with pictures (or only written text), the stories that you and your students love are driven by the moods of the characters within them. Understanding this idea can help you and your students to think about and discuss the stories that you read, watch, or create - deeply and meaningfully. Let’s take a closer look.

For readers, a good indication that they are comprehending the story before them is their ability to answer three simple questions:

What’s the mood?

How do you know what the mood is?

What’s causing the mood?

A good example of this is Peter H. Reynolds’ book, The Dot. If we look at the opening illustration and think about the mood of the character shown, we begin to enter into the heart of the story. Clearly, Vashti, the character we see, can be described as frustrated, upset, or by using another word that connotes a negative mood.

The following visual can help students to home in on the textual evidence that would support their thinking. For instance, students can infer that Vashti is in a sour mood based on her facial expressions, her body language, and the colors that envelop her. That fact that she is not talking, that she’s alone and far away from her desk and other people also shows the negativity within the scene.

Courtesy of Trevor Bryan, Art by Peter H. Reynolds

Based on the textual evidence, the only question we can’t answer with certainty is the third one: “What’s causing the mood?” Peter H. Reynolds does provide some clues as to what could be causing it, but in order to know for sure, the reader would have to read on.

Moving On to Mood Structures

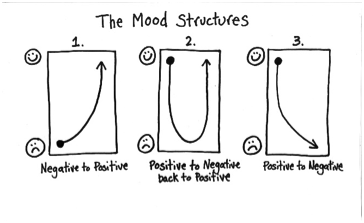

Courtesy of Trevor Bryan

Once readers figure out a beginning mood and what’s causing it, they are in the thick of the story. However, mood is not the only thing that great stories have in common; they also usually have a change in mood.

For instance, in The Dot, Vashti’s mood shifts from frustrated to joyful. Again, Peter H. Reynolds shows this mood change in the illustrations. Using the Access Lenses, students can see that Vashti’s face has changed, her body has changed, the colors have shifted, she is no longer alone, and she is close to her artwork. Paper, which started as a symbol of frustration, flipped to a symbol of confidence, creativity, and joy.

This story’s mood structure can be classified as negative to positive. Understanding basic mood structures helps students to see how stories work, to make predictions, and to recognize key moments. Answering the question, ‘What might cause the mood to change?’ is an easy way to help students to make predictions. And when moods do change, or start to change, it normally indicates a key moment.

From The Dot by Peter H Reynolds, Published by Candlewick Press.

It’s important to note that less complex stories often follow a single mood structure, and in more complex stories—such as novels—the plots and sub-plots will often have different mood structures.

Using Mood and Mood Structures to Support Student Writers

The textual evidence that students pull out of stories to make-meaning is the same kind of information that students can put in to the pictures or text of their stories. The Access Lenses sheet is therefore not just a tool that can be used for comprehension, it can also be used for craft. Likewise, when students use the mood structures to think about the stories they read, they also can use them to think about the stories they create. Below are two general graphic organizers, based on the mood structures, that can help students to plan their stories. For each scene in their stories, students should be able to answer three questions:

What’s the mood?

What is causing the mood?

How can they show the mood?

Courtesy of Trevor Bryan

Courtesy of Trevor Bryan

Stories are built around moods. How characters feel and what drives that emotion is how we connect to stories. Use the Access Lenses and mood to help your students enter into the stories they read (or watch), and to anchor the stories they craft.

About the Author

Trevor Bryan has been an art teacher in New Jersey for the last twenty years. He is passionate about helping students to use the arts to share their unique voices. This post is based on his first book, The Art of Comprehension: Exploring Visual Texts to Foster Comprehension, Conversation and Confidence, which will be out in early 2019 through Stenhouse Publishers. You can contact Trevor through Twitter, @trevorabryan, through his blog, fouroclockfaculty.com, his website, theartofcomprehension.com or reach out through Stenhouse Publishers.

Images from:

The Dot, by Peter H. Reynolds, published by Candlewick Press

The Art of Comprehension: Exploring Visual Texts to Foster Comprehension, Conversation and Confidence, by Trevor Bryan, published Stenhouse Publishers